Will the CRO save software?

A new executive role confronts the uncertainty about how we grow a company.

There’s an ice cream shop a few blocks away from where I live – just far enough that I don’t gain weight in the summer months but not too far for it to be a hassle. Every time I go, they’ve got their standard (blockbuster) flavors. I like the cheesecake. My partner usually enjoys whatever flavor of the month. It’s brilliantly named - “Lik’s” - and has been an institution in Denver for a long time. One of those if-you-know-you-go ice cream shops.

One gorgeous day, when it was partly cloudy with a slight breeze, the line was particularly long. We endured a short wait before I was greeted by a teenager in a branded t-shirt. After a quick survey of the flavors, I stuck with ol’ reliable and then paid. The tables outside were packed, so we decided to walk to the nearby park and enjoy our ice cream there.

As I crossed the street, I wondered: “what would a Chief Revenue Officer do for this business?”

I haven’t had much of a career in the software world. I spent a decade building brands for more profitable businesses, especially the boring ones. Internet providers. Professional service firms. Niche manufacturers.

When I stumbled into B2B software thanks to hosting a podcast, it was very disorienting.

And it wasn't the acronyms. The acronyms are fine. Even your local general contractor uses acronyms.

No, it was disorienting because every company I talked to had the exact same three problems, and very few companies were acting disciplined enough to solve them.

The problems were this:

We don’t have a line of customers out the door

Too many of our customers purchase once, but not more

We’re not sure of the best place to open a new store

A truism of a small business is you can grow a company 30% every year, until you die. You grow the number of customers you have by 10%, you get 10% of your customers to buy from you again, and you increase your pricing (or deal size) by 10%.

Yes it’s tricky and also yes small business owners get in their own way from making this happen, but it’s not magic. It’s math.

In B2B software though, we don’t talk about it this way. We all use this confusing, abstract model. Stage2 Capital discusses “product-market fit” and “go-to-market fit” and “growth and moat.” GTMPartners has “problem market fit” and “product market fit” and “platform market fit.” Every VC firm I can find has some unique flavor of this (my favorite being a surfboard analogy).

And don’t forget the deluge of “-led” models, including community-led, product-led, sales-led, content-led, partner-led, ecosystem-led, marketing-led…

I’m not sure who keeps reinventing the wheel at all of these companies but I hope they’re getting paid well.

The math in software, of course, is very different from the ice cream shop. The basic problem of a software company is that it’s expensive to start but lucrative to run – but the lucrative part only happens after you’ve acquired the customers for long enough. This is the Holy Grail of net dollar retention (or whatever flavor of the month your company calls it). Keep the customers around for long enough and the company becomes profitable!

If it was easy, everybody could do it.

The primary challenge here is that software is more fluid and competitive than an ice cream shop. Ultimately your ice cream shop might start offering takeaway pints, ice cream sandwiches, swag, and other “product lines,” but the bread and butter (or, uh, milk and cream?) of the business is the ice cream.

What if you could change the formula for the ice cream though? And what if everybody else could too?

This is the beating heart of a well-functioning software company. Creating a great product that sells – but also something you can expand and change. Code is very malleable compared to milk and cream. It takes a lot of smart people and smart effort, but building well by solving a valuable problem is worth a lot of money! Eventually!

However, most startups never get past that hurdle and will die.

This is the shakeout happening in B2B SaaS right now. A lot of startups that got funding during 2020-2022 built niche products and sold into one vertical. Now they’re struggling to adapt their product to a more competitive and financially sensitive market.

’s reflection on Groundswell, a startup that offered product usage data, shared the perfect distillation of this challenge:It is more logical for an existing sales platform to introduce product usage signals into their stack, instead of us adding all other signals. Consolidation is becoming a common trend in the market - by joining a bigger platform, we can build a company that is part of a more comprehensive platform.

However, this should be no comfort to more mature “middle market” companies. They are also not safe.

One curious example is Drift’s recent acquisition by Salesloft. It seems that Drift’s failure to get a line of customers seems to have happened because they couldn’t figure out which market to serve.1 They bet on “opening a store” in a new market and… it basically didn’t work? They pivoted their product toward B2C. It didn’t pay off. Meanwhile Intercom, a competitor, bet on “new stores” in customer success and it seems to have worked out just fine.2

Other companies strictly struggle with the basics of getting a line of customers out the door.

In the past five years we’ve invented even more words and abstract concepts to describe this. The many “-led” models, account-based everything, buyer enablement, and the granddaddy of them all: demand generation.

Without doing too much industry-armchair-psychiatry, I would hazard a guess that these have become popular because they provide a small comfort to staff that are trying to navigate a market that has changed substantially in the past five years.

It is harder to get someone’s attention and convert that attention to revenue than it was in 2019.

The things we thought worked no longer work as well.

To get the same results, we send more and spend more.

Less comforting – the same was true in 2013. Seth Godin’s reflection at the time on how the industry had changed since 1998 (!) when he released Permission Marketing feels particularly poignant:

Most big companies now spend far more time than they ever spent before on advertising engaging in its free alternative. They tweet and post and ping and poke and generally put on an ever-noisier show, all based on the self-delusion that they can actually get back to 1968 and the ability to reach everyone, whenever they want. This is obviously a futile endeavor, but it's not stopping people who should know better from trying.

One of the earliest public splashes for the CRO role came in 2012, when Paul Albright – Marketo’s CRO – published a guest post on Forbes.

He wrote about a common business challenge:

While other business processes like distribution have improved by leaps and bounds thanks to supply-chain technology innovation and that old stalwart, Six Sigma, the revenue process is still one of the most inefficient areas of enterprise today. Take this staggering statistic: Forty percent of sales reps' time is actually spent figuring out where to spend their time. If this were the case on a factory floor, where nearly half of a plant’s robots were stuck ‘processing’ where to drive their bolts and welders – there would be some serious retooling of the plant and the company.

Over the past decade, I think his vision of “retooling” the revenue process has broadly come to fruition. Companies now have a pretty standard set of roles & functions. Marketing drives inbound, there’s a few different sales teams to source and close deals, and customer success onboards and renews/expands clients. This was helped along by the popularity of Predictable Revenue (the book) and Hubspot’s inbound model.

In this way, while the software doesn’t resemble ice cream, the operating system of the revenue team sure does. Everyone is playing with the same basic model, but with variations. You might have a ‘Rocky Road’ where account executives are full-cycle and do outbound prospecting. You might have ‘Summer Strawberry’ where marketing boosts your CEO as a thought leader. You may even have ‘Triple Fudge Brownie’ where your account executives hold a book of business and handle renewals.

And yet:

We don’t have a line of customers out the door

Too many of our customers purchase once, but not more

We’re not sure of the best place to open a new store

So what’s going on? Companies have an operating system that’s supposed to generate results but… doesn’t really do it all that well anymore.

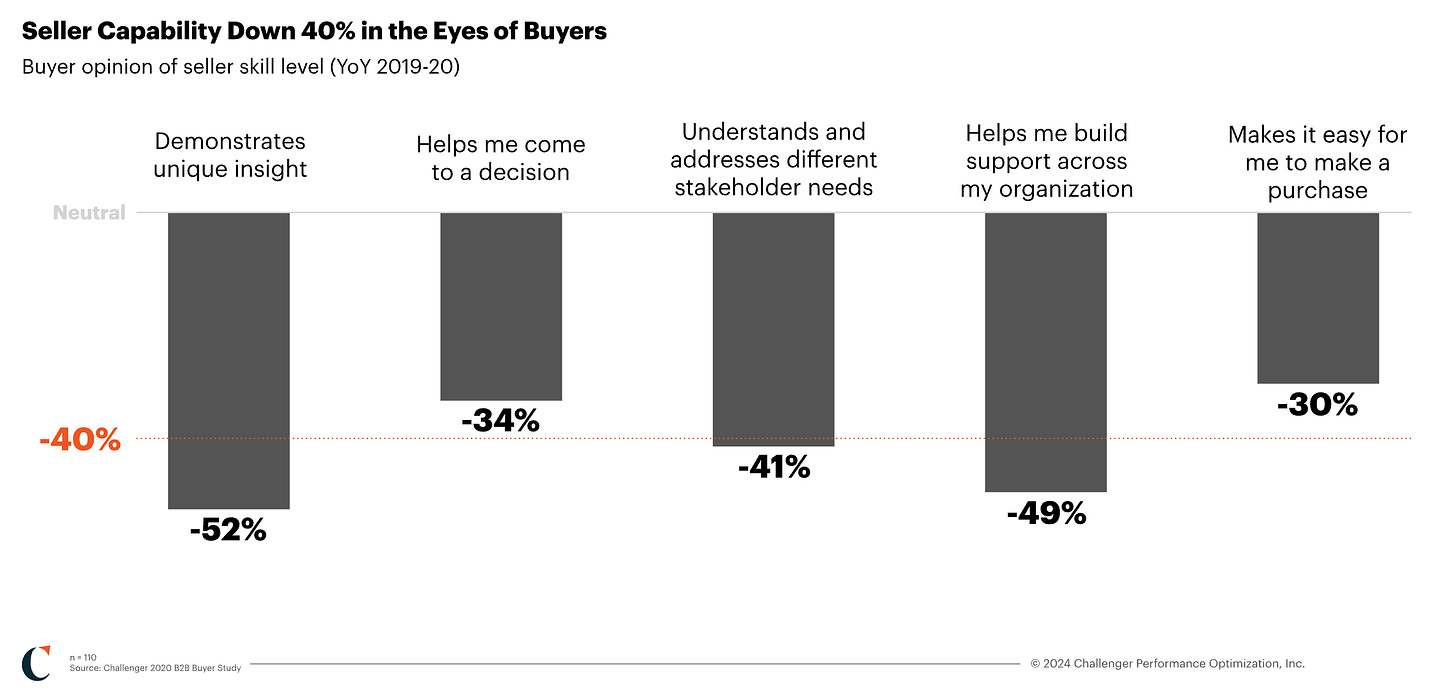

The best diagnosis I’ve seen of this problem comes from Challenger in assessing buyer’s opinion of seller skill level.

They write:

It’s unlikely that sellers have just somehow become less effective in their jobs. Their performance likely didn’t change from 2019 (and that’s the problem). The expectations of their audience have changed. Today’s buyers have real objections, they demand a compelling insight, and they won’t tolerate a meeting that doesn’t engage them and motivate them to action.

Facing a market that has changed will eventually require a “retooling” of the operating system, but the immediate problem is much more drastic.

It’s how the company actually executes.

A client of ours at Tempo sells software into large enterprises in traditional industries like healthcare, financial services, logistics.

One SDR had a Salesloft instance with 17,000 emails sent and 0 responses. The outbound teams generated leads that the AEs couldn’t convert. Marketing hosts webinars and sponsors trade shows, but inbound leads are a trickle. A splashy investment in account-based marketing yielded nothing in one campaign and expensive leads that didn’t convert in another.

The only good news? Once customers bought, they rarely churned.

It may seem like a tragic tale, but they are hardly unique. And this is why I think companies are hiring CROs – to sort out this mess.

This mess is more than just tuning the dials to the exact right place. Sure, there are little tips-and-tricks to improve a cold outbound email or a digital ad. I’m sure you could accurately diagnose the problems I outlined above and improve outcomes. But given how pervasive this problem appears – it’s not just one company, but thousands – fixing it is going to require a different kind of creativity.

I see an “upstream” challenge and a “downstream” challenge for newly hired CROs.

Let’s start downstream: discovering activities that have a high return.

Take Airbnb. A few years ago they decided to stop most of their search advertising spend to invest in brand marketing instead. The results? They’re beating their competitors at it, spending billions less on sales and marketing and still turning a handsome profit. Imagine spending half what your competitors do and still competing toe-to-toe.

Reading through reporting on their decision shows they have a clear internal process to capture data, identify high-return activities, and use that insight to create business strategy.

Most B2B software companies I advise do not have this kind of visibility across the revenue team. They lack the basics of attribution. Even when they have an attribution tool, they rely on poor quality signals to make decisions – i.e. “search” attribution could mean the buyer is searching for your company after listening to a podcast. This would incorrectly attribute success to “search” instead of “podcasts,” which would lead to investing more in low-return search vs. high-return podcasts.

Solving the downstream challenge is a mixture of:

Data centralization - bringing together a 360º view of the revenue team’s output and how right-fit customers are converted and retained

Mapping the buyer experience - creating a visual that shows how buyers tend to interact with the company before purchase

Building real knowledge from data - analyzing the data to separate simple week-to-week variation in the data from actual high-return activities

Fixing gaps - improving team performance through enablement, training, and upskilling

Testing new channels - testing new ways to reach buyers to find new high-return activities

Addressing those challenges should mean a broad portfolio, not a narrow one. I see a few companies creating CROs as glorified VPs of Sales. That’s setting this role up for failure. Incorporating the relevant functions underneath the CRO will be a brave, but necessary, new frontier of senior leadership responsibilities.

It is also a frighteningly big challenge for the newly promoted CRO. There will be some who thrive, but I expect too many to be hamstrung by their organization – or worse, their limited experience.

This brings us to the “upstream” challenge: product strategy.

In this environment, product strategy is going to become synonymous with overall growth strategy. There are ripe opportunities for acquisition. A CRO is a steward of capital, so they should be deeply involved in defining whether an acquisition will make a substantial return.

Similarly, companies may decide to build out capabilities instead of acquiring them. You may not be in the same dead heat race as ZoomInfo and Apollo, but each company is deploying new products to protect and gain market share. Salesforce is starting to box out Gong with Einstein.3 And upstarts offering new AI tech will either die, get snapped up, or need to expand their offering.

This will inevitably create some conflict with heads of product, whether they’re CPOs or VPs of Product, at firms that have reached comfortable success.

In a market where the cost of capital is much lower, the next fundraising round doesn’t seem too hard to achieve, or an inevitable IPO is on the books – sure. Defer to product to lead the way. It can be a very effective way to bring new software to market.

But this market is not like that. Mark Kosoglow (former CRO at Catalyst) reflection is particularly incisive:4

The best weapon against churn is your product → for over 20 years, [customer success manager] super humans have tried to make up for hard-to-use, buggy, complicated, confusing, and impossible-to-understand-the-value products. When you manufacture a lemon of a car, no mechanic can keep it running for long. Many product teams need to be held accountable for churn, not CSMs.

The math of protecting and growing revenue in a software company comes back to net dollar retention – how likely it is for customers to stick around and grow. Product plays a central part, and a really smart CRO is going to help contribute to product strategy decisions.

Of course, there’s a lot of other work to do. It’s mostly downstream. Building processes, leading teams, hiring the right people to enable the team, and integrating the right technology are all at the start of a long list. These are not easy challenges either – they will take a lot of care and attention to do right.

But in 2 years, I expect the companies that emerge with the wind at their backs (and aren’t just zombies of their former selves) will have a CRO who discovered high-return activities and helped guide product strategy.

Ultimately, a CRO might not do much for my local ice cream shop. They already have customers who line up out the door and who return regularly.

But for a software company? They might be their only saving grace.

This is anecdotal, but I know two different sales ops leaders that have disqualified new contracts with niche software companies because it can be solved in Salesforce. One is under pressure from the CFO to reduce tech spend, so they are centralizing everything into Salesforce. They even got rid of Outreach. The other doesn’t see the value in *another* platform to add for the team to figure out. And yes, Gong was disqualified in both cases. Seems like a good market to be Salesforce.