GTM leaders are brand managers without any of the authority

The old-school brand manager model is making a surge in B2B under a different name

There’s a funny Reddit thread titled “k wtf is go to market? everytime i try to read about it just sounds like marketing”. The Redditor writes:

The context i often hear it [used] is when we're looking at a couple product lines for my company and it's poor performance in the last year and someone says that we may have a gtm issue. i don't really understand that.

And the comments are pretty much what you’d expect. They’re all over the place. One user writes:

GTM = marketing + sales (incl. any channel partner activity) + customer success (or account management).

Another:

We also use it to describe putting out a tender process to suppliers.

And:

In my company is used to refer to Sales.

I sympathize deeply with this Redditor because a quick glance at existing resources even has me scratching my head:

If I walked into a board meeting of a client and said “here is my marketing plan for your product for the next 12 months” and they said “what about your strategic outline of the concrete steps required to bring our product to the marketplace” and I said “yes that’s this marketing plan” do you think I’d get fired?

If you were lucky enough to be subscribed to the CIO Enterprise magazine in 1999 and you picked up the May 15 issue, you might have read a small entry on page 20 titled “Call Me”:1

Electronic commerce is growing faster than Jack’s beanstalk. But a recent study titled, ‘The Role of the Telechannel in Go-to-Market Strategy,’ by Oxford Associates Inc. of Bethesda, Md., reminds executives that good old telephone still needs to be part of every ‘go-to-market’ strategy – how companies integrate and deploy sales and marketing resources to reach their markets.

This is actually one of the first times a publication explicitly references “go-to-market strategy” as something a company has.2

It joined a small group of books released between 1998 and 2002 with titles like “The Complete Guide to Accelerating Sales Force Performance” and “The Channel Advantage” that began evangelizing this concept.

You get some truly great stuff from that era:

We live in a world of rapidly increasing go-to-market choices, many of which were created by recent technological advances. These choices have enabled today’s successful business carnivore – the aggressive integrated multi-channel organization, the scary one who’s actually figured out how to make sales reps, partners, the phone, and the Web all work together – to devour the friendly plant-eaters dressing up in suits and calling on their customers one at a time to talk about golf and the kids.

That’s from “Go to Market Strategy,” a 2002 book.

We all know how this turned out… companies became the carnivores!

They adopted CRMs, built out predictable revenue engines using specialized sales teams, created inbound traffic from a content marketing engine, and they devoured (I want you to read that with a real grrrr) the competition. The plant-eaters lost.

The Internet forced companies to start developing a real channel strategy because there were so many channels available – direct sales channels, indirect partner channels, telechannels, the Web, email, digital ads. Go-to-market became “integrating” and “deploying” resources into these channels to reach their target buyers.

And at the exact same time, cloud-enabled software brought a major shift in B2B sales. The expansion of software offerings beyond IT departments meant that companies could target multiple business units as potential customers.

It’s a simplification (but a true one!) that B2B sales used to just be “nerd sales” because you only needed to advertise in the one trade magazine that existed for, I don’t know, steel pipe fittings. The purchasing manager who cared about steel pipe fittings at a large industrial buyer would then read the magazine and call. B2B firms didn’t have the large, disparate base of customers that we have today.3

That changed. In 1983, Ogilvy even wrote:

In industrial companies there are an average of four ‘buying influences.’ Your sales force is unlikely to know all four. Sixty per cent of ‘specificers’ – people who set down the specifications that must be met – read advertisements to learn what’s on the market.

Out with the singular purchasing managers, in with the buying committee. When cloud-enabled software took off, those buying committees expanded beyond simple “specificers” who controlled what specifications needed to be met. So companies now had:

Specialized channels that needed to be integrated

Specialized teams that needed to sell to multiple buying influencers

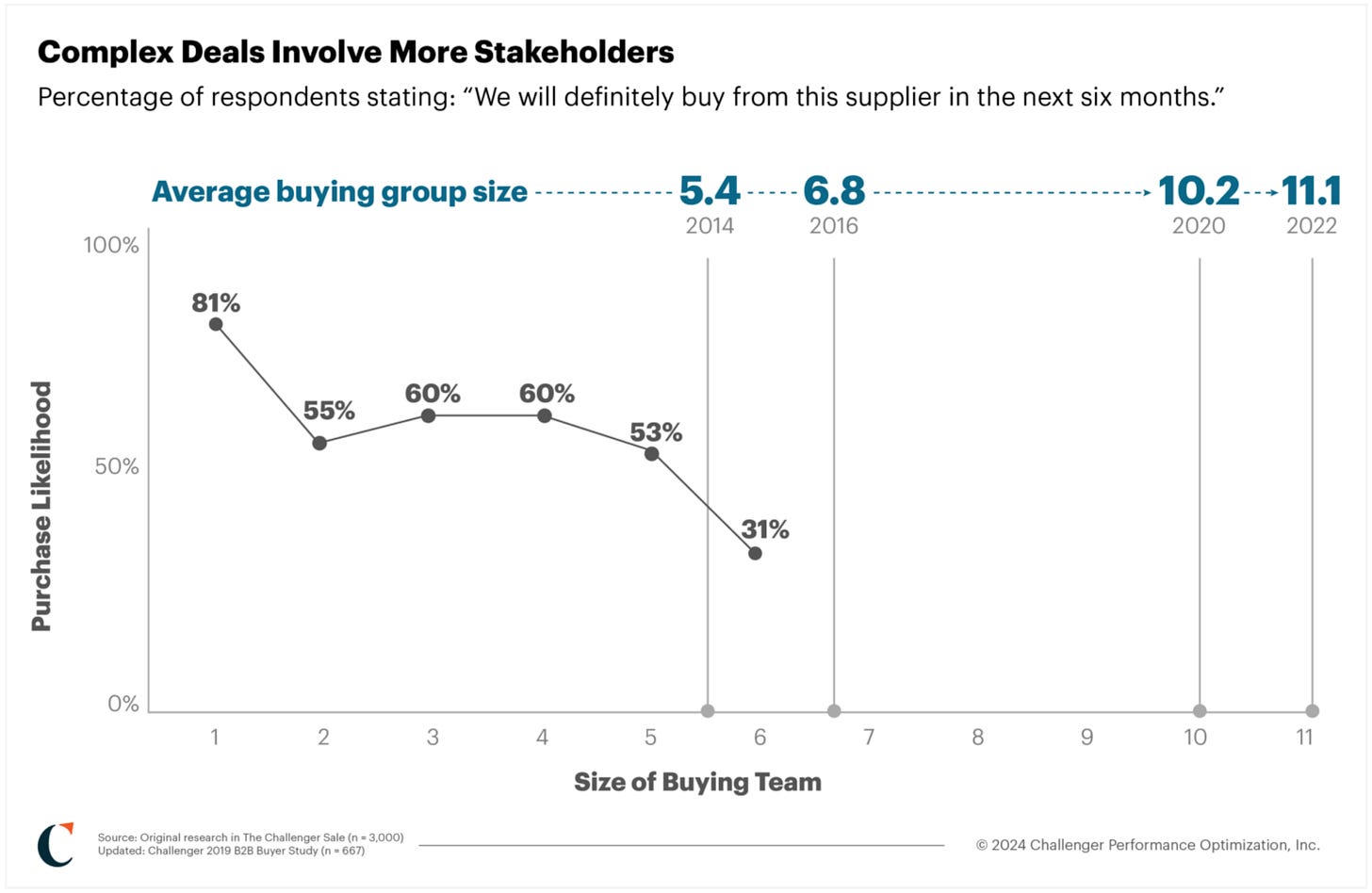

And in 2014, Challenger benchmarked an average of 5.4 people in a buying committee. In 2022, it was 11.1. They map this problem neatly below: the more people you get involved in a deal, the less likely it is to succeed.

So some poor, newly hired Chief Revenue Officer in 2024 has to figure out a go-to-market strategy that answers:

Which markets for each product

Which buyers in each market

Which channels to reach those buyers in each market

How to “integrate and deploy sales and marketing resources to reach their markets” across each channel

How to figure out what messaging works to avoid “no decision” when you’ve got 11.1+ buyers because obviously most deals are never going to close when 11.1+ buyers are involved

Support sales reps to use the messaging and techniques to avoid “no decision” when there are 11.1+ buyers are involved

Scale it up for every market the company targets

It’s no wonder companies like S&P Global are putting out job descriptions for a “Head of Go To Market and Market Development, Americas” that read like a wishlist, not a job description. This is an insane portfolio of work:

They will work closely with cross-functional teams, including Commercial (sales and product specialists), Product, and Marketing, to achieve business targets, monitor market trends and competition, and support the evaluation of partnerships to accelerate penetration and adoption of [our] offerings.

They are responsible for Go-To-Market initiatives in the Americas - including thought leadership, field readiness for new products and feature launches, development of event strategy, voice of customer, and competitive intelligence – and for various operational and strategic initiatives across a year.

But also, is this any different than an old school brand manager without any of the traditional authority of a brand manager?

In 1982, Tom Peters wrote In Search of Excellence with Robert Waterman as a response to the popularity of the McKinsey 7S framework (which he helped develop).

He identified eight qualities that made some companies truly excellent by measuring their financial return over a period of time. All were mushy, non-quantitative principles. Number 4 was “autonomy & entrepreneurship.” He writes:

We next encountered the phenomenon at Dana, where chairman Rene McPherson invented the “store manager” concept. Practically speaking, it meant giving his approximately ninety factory managers lots of authority. They had unusual control over hiring and firing; they had their own financial control systems; they did their own purchasing – all tasks that are normally centralized.

The same concept goes by the name “brand manager” at Proctor & Gamble and Frito-Lay.

The brand manager concept is a simple idea. There’s a person who is accountable for a brand like Tide or Pampers. They lead the entire “go-to-market” strategy from product design and R&D all the way to growing its market share. They are a de facto business unit head with internal authority to make investments, market, and reposition.

I think B2B companies that have charged past their first $10 million in revenue are stuck in a strange position and not entirely sure how to get out of it. Having read about 120 job descriptions over the past week for GTM leaders and CROs like the one above, it seems like:

For the past 15 years, they operated in a “specialized teams for specialized channels” model that made them a lot of money.

These specialized teams might have worked on a particular product line, but they reported up inside their own function. Specialized outbound teams reported up through the VP of Sales. Specialized digital advertising teams reported up through the VP of Marketing/CMO.

Now that getting a B2B deal across the finish line is much more complex, requiring many more touchpoints with many more buyers, they recognize they need a person to “work closely with cross-functional teams” (which is corporate-speak for, you know, herding cats) in order to improve their top-line revenue. That person would see things that a specialized team member wouldn’t and offer helpful fixes for the product, the marketing, and the sales process.

That person cannot hire, fire, make financial decisions, or otherwise invest company resources without somebody else’s approval.

Like, I get it! It’s probably not ideal to tell your VPs that the authority they have worked very hard to obtain no longer matters as much. It’s also probably true that it’d be hard to find a “brand manager” in B2B with a similar interdisciplinary skillset that P&G hires for. We train specialized marketers who know product marketing (but not how to run an ad on LinkedIn) and specialized salespeople who know how to navigate complex buying committees (but not how to make a 1-3 year investment strategy in product R&D).

But companies are still hiring GTM leaders who are nominally supposed to “partner with global sales team to align product and market strategy with GTM execution plan.” That sounds a lot like a brand manager who doesn’t actually have the authority of a brand manager!

It’s possible some companies are actually hiring these GTM leaders as brand managers. But if they turn out to be brand managers without authority, I’d expect organizations to constantly run into three problems.

Who makes the final call?

In every GTM leader position, there’s a line that reads something like this:

Collaborate with cross-functional teams to identify and capitalize on market opportunities.

In software, that means building new products! A market opportunity means writing code, developing positioning, and sharing the good news with the prospective buyers. But the product roadmap is the domain of the product team. And the product marketers that would build positioning don’t report to the GTM person, they report up to the VP of Marketing.

So when this GTM leader who is expected to capitalize on market opportunities has an idea for a new product or feature… how much time do they have to wait for everyone to approve it? Does it get escalated all the way to the CPO or CEO every time? Does the launch campaign get prioritized over other product marketing tasks with… or without the VP of Marketing’s input?

I have unfortunately seen this problem up close. It’s messy. It becomes territorial. There are a lot emotions and resentment flying around with competing priorities and the CEO often becomes an arbiter. It can become so toxic that you’ll end up with sentiments like this, sent from a friend – “The situation is too dysfunctional to try and administer logic.”

Who orchestrates the campaign?

Here’s an excerpt from another job description:

Coordinate product launch activities, ensuring all elements are aligned for a successful market entry. This includes sales training, marketing collateral, promotional campaigns, and customer feedback loops.

Collaborate with Product, Supply Chain, Marketing, Sales, Legal/Finance, and Customer Service teams to ensure seamless execution of GTM strategies. Lead cross-functional teams through product launch processes focusing on commercialization.

Launching a product and growing it is, like, what brand managers do. But here, this GTM leader is expected to “coordinate” and “collaborate” with other teams. So who’s the Executive Chef? Who’s the Expediter? Who’s the Line Cook? Who’s actually building and monitoring sales scripts or ensuring advertising is deployed on time? (Issue #1 pops up here too) Does the GTM leader have a dashboard that intersects with every other team at the company? Do they even have any authority to hold other team members accountable for deliverables?

Product marketers have generally led the charge in B2B software for product launches because we haven’t historically had brand managers. But in hiring these GTM leaders, it’s obvious to me companies are thinking about the problems a brand manager could solve as something separate from the product marketer role.

Maybe the GTM leader shouldn’t “coordinate” by “collaborating” with other teams! Maybe they should just own the P&L!

Who gets fired?

Obviously the sales team, I mean who else could it be? The VP of Marketing? Ha! Yeah right.

There might be a more nuanced answer here. There’s been a lot of hubbub over the last 2-3 years on the high turnover rate of VPs of Sales and CROs. Whatever number you end up at – 18 months average turnover, 24 months, 19 months – it’s pretty clear something is afoot.

First off, it doesn’t seem like these same figures apply to Fortune 500 companies where C-suite executives last 4 years or more, on average. If I had to guess, I’d say it is because C-suite executives usually are tasked with market share, not just top line revenue, and improving market share in a Fortune 500 company is a multi-year endeavor.

Whereas startups, scale ups, and the middle market have much higher, short-term pressure for top-line growth. Why turnover is so comparatively high probably has multiple causes, but I could imagine something like:

A VP of Sales or CRO is hired with a plan of action to scale up revenue of the team

It kinda works

But also it doesn’t work as well as they promised or as well as what the board wants

They’re fired or forced out

This appears to be a sad irony, then. A lack of authority to make a final call and run campaigns will hamstring the rollout of the overarching GTM strategy.4 So in this case, actually, a GTM leader without authority might survive multiple CRO turnovers because the executive is the person on the line. A lack of real authority for the GTM leader also means a lack of real accountability.

Obviously a “brand manager” role assumes that a company has multiple brands. That is not always the case. But I could imagine three different scenarios:

A company with one major product line that sells into one or two industry verticals with the Chief Revenue Officer or a Director of GTM Strategy as the de facto “brand manager” (they would own the P&L)

A company with multiple product lines that sells into one or two industry verticals. In this case, there should be a “brand manager” for each of the product lines. In less mature organizations where there isn’t the interdisciplinary skillset, you might pair a business unit head who owns the product roadmap and P&L with a “brand manager” type (like a Director of GTM strategy) who owns the marketing and sales function.

A company with multiple product lines that sells into multiple different industry verticals. In this case, you’ll want a “senior brand manager” role to own each product line and a “junior brand manager” role to run industry-specific GTM strategy. You might also have a business unit head who owns the product roadmap, but at this point there aren’t too many meaningful distinctions.

Larger companies will fall into buckets 2 and 3 while smaller companies, or startups who reached exit velocity, to fall into buckets 1 or 2.

Basically, as the company is scaling, they are “unbundling” the responsibilities of the CRO to GTM leaders for each product line. Companies basically inherit the “cross-functional” model from when they only had one major product line with a couple industry verticals. Expanding product suites or target verticals should mean new ownership for each line of business, not more cross-functional work.

This model may not work for every company. It took P&G more than 100 years before they rolled out their brand manager model. But I would expect newly hired GTM leadership to incur more wasted time and more headaches without a change to the existing model. More collaboration is not always the cure.

Sadly, I was not, but the internet has preserved it for posterity.

This Google N gram is particularly instructive: go-to-market is a neologism from 1995-on, whereas most business leads are very used to “marketing strategy” or “sales plan” by comparison.

This was the era known as “trade advertising” or “industrial advertising.” Although my favorite little tidbit about inbound sales from this era comes from a McGraw-Hill study in the '70s that showed “nearly all inquiries come from people who have a specific need or application in mind; and a substantial percentage of them buy within six months of their inquiry.” I wonder if there’s a certain psychology in group buying that leads to this 6-month figure, because it seems like most deals at most software companies still generally take 6 months to close.

In a startup environment, this is less visible because the CRO is the one making all of the calls. It’s really only once you get to multiple product lines or selling into multiple verticals that this would happen, which funnily enough is when these companies seem to be hiring for GTM leaders.